By Leanna Stoufer, CCASA Guest Blogger

I recently returned from a month-long volunteer abroad program in Dharamsala, India—literally half-way around the world from my home—which is an amazing accomplishment for this survivor-of-multiple sexual assaults and relationship violence. My experience is that the assault that happened when I was 14 left me feeling so ashamed that I kept it to myself for decades. The silence just about did me in, and I spent much of my life withdrawn, afraid and suicidal. It was not until 2008, after another assault which was nearly fatal, when two victim advocates arrived at the emergency room and literally saved my life. Through listening, believing me, not judging, and telling me that it wasn’t my fault (along with sharing resources), they set me on a path of healing. Among all of the amazing experiences in India, listening to the refugees’ stories was one of the most life-changing, perhaps because it touched the soft heart of my own experience.

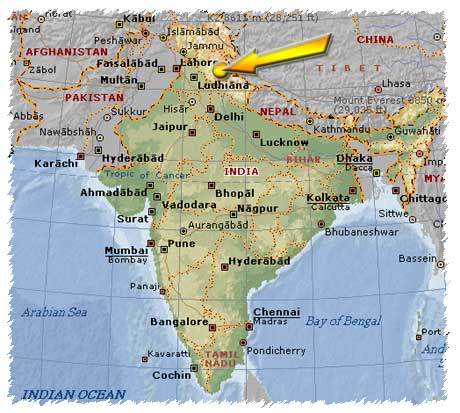

I recently returned from a month-long volunteer abroad program in Dharamsala, India—literally half-way around the world from my home—which is an amazing accomplishment for this survivor-of-multiple sexual assaults and relationship violence. My experience is that the assault that happened when I was 14 left me feeling so ashamed that I kept it to myself for decades. The silence just about did me in, and I spent much of my life withdrawn, afraid and suicidal. It was not until 2008, after another assault which was nearly fatal, when two victim advocates arrived at the emergency room and literally saved my life. Through listening, believing me, not judging, and telling me that it wasn’t my fault (along with sharing resources), they set me on a path of healing. Among all of the amazing experiences in India, listening to the refugees’ stories was one of the most life-changing, perhaps because it touched the soft heart of my own experience.

This blog is not about my survivorship, however, but about the many Tibetan refugees and other students who shared their experiences and dreams with me. This is also about my face-to-face discovery of cultural values and ideas that are very different from those we have in the United States. As a volunteer, one of my assignments was to attend the morning conversation class at Tibet Hope Center, where one volunteer and a small group of students would be given topics around which to learn new vocabulary words and practice sharing their experience and opinions in discussion.

Despite my interest in the situation in Tibet over the last decade, there was no great push on my part to press for details on what these people endured in their journey from their former lives to their current lives as refugees. Nor was there any apparent need for any of them to “tell their story.” In many ways this made the pieces that they shared even more poignant and precious for me. Instead, it was simply through the course of discussing the daily topics that we were given, and in answering the discussion questions, that I began to understand what so many of the refugees had been through.

Our topic one day was “travel” which then led to where those in my group that day had traveled and how they had traveled. Among my students that day was a Tibetan monk named Tenzin, a quiet man, with a quick smile and a gentle sense of humor. When it came to his turn to share, he said that he had traveled to India of course, and had been to Nepal. It was right after class, while we were continuing the conversation, that he told me a little about walking through Tibet, through the Himalayas during the coldest part of winter, with one friend, another monk. It is important to travel when the conditions are the worst, because there are fewer Chinese patrols then. He said that it took them about a month to make their way to Nepal. They had to be very careful to not be seen by anyone on their trek, and could not risk talking to anyone along the way—not even another Tibetan, because there are many Chinese military police that can pass for Tibetans and one never knows who they might be talking with. Even if the other person were a Tibetan, and not a spy, it is terribly risky to let anyone know that one is trying to escape—it puts both the travelers and the person they talk to at risk.

Our topic one day was “travel” which then led to where those in my group that day had traveled and how they had traveled. Among my students that day was a Tibetan monk named Tenzin, a quiet man, with a quick smile and a gentle sense of humor. When it came to his turn to share, he said that he had traveled to India of course, and had been to Nepal. It was right after class, while we were continuing the conversation, that he told me a little about walking through Tibet, through the Himalayas during the coldest part of winter, with one friend, another monk. It is important to travel when the conditions are the worst, because there are fewer Chinese patrols then. He said that it took them about a month to make their way to Nepal. They had to be very careful to not be seen by anyone on their trek, and could not risk talking to anyone along the way—not even another Tibetan, because there are many Chinese military police that can pass for Tibetans and one never knows who they might be talking with. Even if the other person were a Tibetan, and not a spy, it is terribly risky to let anyone know that one is trying to escape—it puts both the travelers and the person they talk to at risk.

At this point, I asked Tenzin if it was a relief to finally reach Nepal; he lowered his head for a moment and said that was the most lonely part of the journey. First of all, Nepal is no longer a safe zone for Tibetans escaping Chinese government oppression. Second, Tenzin said that he had expected to find other Buddhists there that would support and encourage he and his friend. They thought they would finally be able to practice their rituals and prayers, and instead, they found no help in this area whatsoever. Tenzin and his friend made it to the Tibetan Reception Center in Kathmandu, and within a few weeks were on their way to Delhi, and then to Dharamsala. He said that once they reached Dharamsala they were at least among others that practice their particular school of Buddhism, and of course, they were finally near their spiritual leader, His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama.

Tenzin went on to say that his friend decided to return after a few months; perhaps it was homesickness, or perhaps just not being able to settle into such a different location and lifestyle. Regardless, his friend left, and Tenzin has not heard from him since; he does not know if his friend is alive, or dead, or imprisoned.

What was most striking about Tenzin’s story is that he was so very open and willing to share his experience, yet there was no sense of blame, or justification, or apology, or self-pity. He simply shared the facts of what his experience had been. Here was a man, face to face with me, whose life had been shattered in every respect –loss of family and community, loss of home and of his way of life, loss of his very identity as a Tibetan citizen and as a Tibetan Buddhist—all through the unwarranted actions of a foreign government. Yet, he had refused to let this break his gentle spirit, and instead embraced his resiliency and practiced the very things that make him who he is – gentleness, compassion and humor.

This same honesty, forthrightness and acceptance came shining through similar discussions with other refugees. This was noticeable to me because my own journey toward being able to talk about my experiences was so long, and the judgment that was leveled against me the first few times I attempted to share pieces of my story left me feeling re-victimized and worse than remaining silent. It took a great deal of energy, effort, and therapy, to come to a place where I could “own” my experience and talk about it without re-igniting the anger and shame.

The contrast between how many of the Tibetan refugees related their experiences, and what I see in my own journey and that of many other survivors here in the West, seems to hinge on the cultural attitudes of supporting the victim (within the Tibetan community) and those of blaming the victim (here in the United States). Within the Tibetan community, and even in the Indian government’s welcoming the Tibetans, there is no sense of judgment and no blaming. The refugees are not interrogated about how they may have caused their ill-treatment, and they are not blamed for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. There are many factors, of course in how individuals deal with their trauma, but overall, it seems that this attitude of non-blaming allows at least most of the refugees a way to own and integrate their experience. By contrast, much of the United States is still entangled in thinking that a sexual assault or domestic violence survivor must have “done something wrong” or the violence would not have occurred. Progress in this area is being made in the West, but we have a long way to go before society’s default response is to support the victim.

I need to add a caveat here, because there are many human rights, and particularly women’s rights, issues in India that are only beginning to be addressed. Certainly India is nowhere near being a utopia where equality and justice are supported across all groups. But then, neither is the United States, and as a nation we have far more resources which could be allocated for protecting our most vulnerable citizens. The reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act, earlier this year, was one step in the right direction, and we need to continue building on that success.

In relating the calm way that Tenzin shared his story, I am not saying that survivors should avoid expressing the anger and outrage of being assaulted, for that was actually a turning point in my own healing, and a huge piece of reclaiming my life. However uncomfortable others may have been with me expressing my anger, it was tortuous for me to try to contain it over the years between the first assault and the last one which finally brought me in contact with trauma therapy. My opinion is two-fold. First, that Western culture might be able to learn something from a way of being in the world that allows space for a survivor to own their experience and express their resiliency without hushing up the problem. And second, that as survivors, we can work toward a place where we can own our experiences—even those most horrific experiences, integrate them, and go on to reclaim ourselves, including the most powerful, beautiful expressions of our spirit, in our daily lives.

Leanna, what wonderful and beautiful stories you have woven together to bring a NO JUDGMENT/NO BLAME reality check for a spiritual way of living. We are not victims, who have done something wrong — we are Children of God, who have experienced hardships of mass proportion. Owning our experiences and reclaiming our true selves, without shame or guilt is right on!